(Chelsea Update would like to thank Tom Hodgson and the Waterloo Area Historical Association for the information in this story.)

The first settlers to arrive in the Chelsea area found it to be a very different place than we see today. Water levels were 4-6 feet higher and so much of the area was covered by wetlands it was known as “the land of the black swamps.”

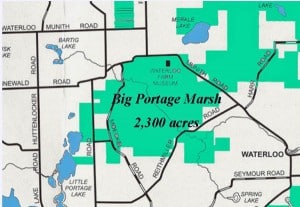

The “mother of all swamps” was Big Portage Marsh located just north and west of the town of Waterloo. Even today, it includes over 2,300 acres of continuous wetlands. The marsh was also the headwaters of the Portage River, a winding, meandering stream that eventually flowed into the Grand River.

In those days, marshlands were considered useless unless they could be drained and converted to farmland.The Army Corps of Engineers dredged and straightened the Portage River, lowering local surface water levels some 4-6 feet exposing more land for agriculture.

The loss of wetland habitat was detrimental to many wildlife species, some disappeared completely, while others remained as only remnant populations.

By 1942, a once thriving sandhill crane population had been reduced to just 17 pairs state-wide. Fortunately, since legislation now protects the majority of our remaining wetlands the sandhill cranes and other marsh-loving species have been gradually coming back.

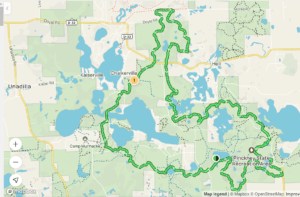

Silt, downed trees and other debris have accumulated in the river over years and now impede water flow considerably. The Corps of Engineers has decided that re-trenching would not be cost effective, so the river is being left to revert to a more natural state. Once again, the river spills over its banks in spring and during wet years. Much of the land along its route is no longer drained or tilled and is reverting to riparian wetlands, creating important wildlife habitat.

Silt, downed trees and other debris have accumulated in the river over years and now impede water flow considerably. The Corps of Engineers has decided that re-trenching would not be cost effective, so the river is being left to revert to a more natural state. Once again, the river spills over its banks in spring and during wet years. Much of the land along its route is no longer drained or tilled and is reverting to riparian wetlands, creating important wildlife habitat.

Waterfowl, bald eagles, herons and egrets are moving in, as are the two most aquatic members of the weasel family, the mink and river otter.

American mink are frequently seen swimming in the Portage River, and running along banks, fallen logs and even climbing trees. Their elongated bodies allow them to follow prey into holes and burrows.

They swim well enough to catch amphibians, small fish and crayfish. These mink also eat birds, eggs, and small mammals, and are formidable predators of muskrats, which are chased underwater and killed in their burrows.

American mink depend primarily on eyesight to locate prey, and have a rather weak sense of smell. They live in dens consisting of long burrows in river banks, holes under logs, tree stumps or roots, and occasionally in hollow trees.

River otters are highly aquatic.They are equipped with webbed feet and extremely dense fur, which is essentially water proof. In addition, they have a thick layer of fat under the skin that further insulates them from the cold water and cold weather of winter. They can also close their ears and nostrils while diving to keep out the water.

River otters are active year around. Powerful lungs allow them to swim up to 1/4 mile underwater at speeds up to 6 miles per hour, and they can hold their breath for up to 8 minutes.

River otters appear to be playful animals, exhibiting behaviors such as mud/snow sliding, burrowing through the snow, and water play. However, many “play” activities actually serve a purpose. Some behaviors are used to strengthen social bonds, to practice hunting techniques, and scent mark.

River otters get their boundless energy from a very high metabolism, which also requires them to eat a great deal each day. They eat mainly aquatic organisms such as amphibians, fish, turtles, crayfish and other invertebrates. Birds, their eggs, and small terrestrial mammals are also eaten on occasion.

At least one pair of river otters now make the Portage River their home and have been seen with increasing frequently. However, they have such large territories that it is impossible to say where they might be at any given time. And, because the river is now so choked with fallen trees, it is very difficult to navigate, even in a kayak or canoe.

This article and these very nice pictures brought back memories. During the Great Depression of the 1930s my father supplemented our meager agricultural income by trapping mink and selling the fur. A prime mink pelt brought about $60 — a princely sum in those days.

Thanks, Tom, for the article.

This is wonderful!