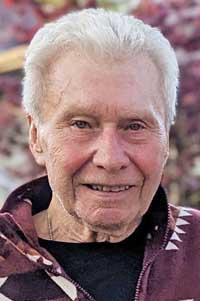

Story and photos by Master Naturalist Doug Jackson

“Beneath this snowy mantle, cold and clean,

The unborn grass lies waiting for its coat to turn green.

The snowbird sings the song he always sings,

And speaks to me of flowers that will bloom again in spring.”

The opening lyrics to Snowbird by Gene Mac Lellan.

With its catchy train-song rhythm and sweet melody, it’s no wonder how recording that song about a little winter sparrow would launch Anne Murray’s singing career back in 1970. If you’ve forgotten or are not familiar with that song, I encourage you to take a break now and treat yourself to listening online to her recording of that hit.

The snowbird is one nickname given to one of the most common new-world sparrows in North America, the dark-eyed junco, junco hyemalis.

The “song he sings” is a high monotone musical trill, and his call can either be a quiet little high-pitched pick or a high metallic tew tew tew.

This species is highly varied across the continent. It has five subspecies whose geographical regions are distinct for most of them and can also overlap.

Here, in Michigan, we have the most common subspecies, the slate-colored junco, that arrives in late autumn and, for some, signals the arrival of winter and promise of a “snowy mantle.”

In other regions of the country further west, we find the four other subspecies, the gray-headed, Oregon, pink-sided, and white-winged.

The slate-colored subspecies can be found throughout the lower 48 in winter. However, just before the flowers “bloom again in spring,” these little snowbirds fly back to Canada to their breeding grounds for the summer.

The slate-colored subspecies are named for their own unique and easily identifiable plumage. Though being dimorphic, the male and female juncos have a different appearance.

The males have a very dark slate-colored body with a boldly contrasting white belly. They also have white outer tail feathers that make them unmistakable when they flit off from beneath your feeders or out from amongst the forest understory.

The females have a similar but less bold appearance, being a lighter gray with some brown on their backs. Both male and female juveniles look almost identical to their mothers.

Don’t feel cheated if you’re noticing mostly just the darker males. The majority of our juncos are male with only one out of five juncos in Michigan being female.

So where are all the females? Let’s just say that those folks down south in places like Alabama see mostly the lighter juncos, and very few males.

It turns out that several bird species, including the dark-eyed junco, tree sparrow, song sparrow, and mourning dove, exhibit an interesting and not fully understood migratory behavior. During winter migration, the males will not fly as far south as most of the females.

Hence, in northern states, most of our snowbirds will be male, while in the south, most will be female, and in central states such as Tennessee, there will be an even mix of the two sexes.

This behavior is most obvious with the juncos because the other species mentioned earlier are not dimorphic, that is, the males and females of those species are virtually indistinguishable in appearance.

So why do they migrate like this? Why don’t all the males go as far south as the females? Perhaps to truly know, we’d have to ask one.

To postulate, there could be several competitive advantages for these species to migrate as they do. Firstly, a shorter migration uses up a lot less of their energy. Plus, the males will have less competition for food in the northern states. Just think of all those other birds flying south to Dixie for the winter.

The males are adapted to handle the colder winters in the north better than their better halves. The males are slightly larger than the females and, because of what’s known as Bergmann’s Law stating that larger endothermic (warm blooded) animal bodies retain heat longer, the males can tolerate longer periods of cold weather.

Plus, being larger, the males can survive about 4% longer without food.

In addition, when spring arrives and birds head back north, the males that are closest to their breeding grounds will have the advantage of being first to stakeout their territories and successfully attract their mates.

Sadly, we have seen a huge reduction in bird populations over the past several decades. Bird strikes with windows in houses and high-rises have claimed as many as a billion birds in a year. This, combined with habitat destruction, light pollution, disease, predation from house cats, and competition from invasive species has taken a huge toll on our feathered friends.

Though the dark-eyed junco remains a very common sight, and one of the most popular birds, since the time Anne Murray first recorded Snowbird, they have lost over 40% of their numbers.

We can do our part to help not only feed our birds but to protect and improve their habitats. Replacing large lawns with smaller lawns with native landscaping that provide food and cover can make a big difference for birds and other wildlife, as does supporting any legislation that protects species and their habitats.

With our help, our birds can continue their singing careers for time to come.

I would think that after Anne Murray sang the words, “And if I could, you know that I would fly away with you,” that she realized those words as her career was propelled skyward which could only approximate the prolific singing careers of these little snowbirds.