(Chelsea Update would like to thank Tom Hodgson and the Waterloo Natural History Association for the information in this story.)

Evidence of the presence of the human species in our area dates back about 10,000 years.

This roughly coincides with the end of the last Ice Age. Any evidence of human activity prior to that time was destroyed by the advancing glaciers. Fluted projectile points found in the area tell us that Waterloo was first occupied by ancient peoples who killed pre-historic elephant-like giant mastodons. And, mastodon teeth and other skeletal remains have been unearthed by local farmers. These ancient peoples were gradually replaced by modern tribes.

The most of the modern tribes were of the Algonquin language group, the most prominent being the Potawatomi, Chippewa, Ottawa and Sauk. The Wyandotte of the Iroquoian language group were also present for a short time. In fact, the Waterloo area was commonly used as hunting grounds by the Algonquin. Other than a few foot trails, Native Americans made no notable changes to the landscape.

Although they planted a few crops such as corn and squash, they primarily subsisted on what they could hunt or gather from their environment. The only things they left behind were their stone tools that were discarded, broken or lost. These included spear points, arrowheads, knives, axes and scrapers as well as body ornaments. They probably would have never been seen again, if they had not been unearthed as farmers tilled the soil each spring.

Farm children were often assigned to walk behind the plow to remove rocks that were unearthed to improve the soil. In the process they found native artifacts as well. They collected them primarily as curiosity pieces, but thanks to the interest of J. Vincent Burg I, a local Chelsea Pharmacist, they also had monetary value. Mr. Burg had a life-long interest in native artifacts. He and his family looked for them each spring, but Vince also discovered that he could enlist the services of local farm children if he traded their caches of artifacts for ice cream and sodas at the pharmacy’s soda fountain. The pharmacy was located in what is now Zou Zou’s sandwich shop.

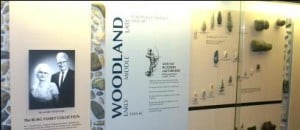

Over the years, he amassed a collection of over 2,000 pieces and displayed them on specially made “arrowhead-shaped” shields in the pharmacy. The University of Michigan expressed some interest in the collection, but Burg wanted the collection to remain local so that all could enjoy it.

This is where this author became involved. At the time, I was the park interpreter (naturalist) for the Waterloo Recreation Area. I was approached by the Burg family in the early 1970’s to see if the soon to be constructed Waterloo Nature Center could be a home for the collection. I knew very little about native artifacts at the time, but was eager to learn.

I took some of the representative pieces from the collection to the U- M Museum and they told me what they were. I found that some of the earliest pieces were made by Paleo Indians that lived in the area soon after the glaciers retreated, and the newest pieces were still about 500 years old. Most were not “arrowheads” at all, but were knife blades, spear points, axes and hide scrapers.

I mounted these representative pieces on Masonite shields and used them for teaching purposes. I took them to local historical society meetings. My visits would be announced in advance and local farmers and farm children, who were still collecting these artifacts, brought their caches to compare with my samples. It was a lot of fun and I was amazed at how much interest and enthusiasm they generated.

The collection was formally donated to the DNR in 1973 to be displayed in the soon to be built Waterloo Nature Center. The building was open in the fall of 1977. The Center has gone through many name changes over the years and is now known as the Gerald E. Eddy Discovery Center. The Burg collection has survived all the changes and is proudly displayed in its entirety.

If you haven’t seen it, you need to. This may be the only opportunity to discover this fascinating period of local history. If you happen to have some “arrowheads” stashed in a jar somewhere, bring them along. You’ll be able to find out what they really are.